Roughin' It

Growing up in rural New Hampshire, the Nelson brothers developed a deep appreciation for nature. Regularly exploring its wonders, they learned to hunt, fish, berry, navigate, construct shelter, and otherwise hold their own in the wilderness. These cherished adventures often surface as the raw material for the Nelson brothers’ stories, figuring as heavily in their imaginative play as in their physical pursuits, and affording their narratives the kind of tactile, experiential authority that one can only glean firsthand – or as the brothers might say themselves, by “roughin' it!”

Throughout the Nelson brothers’ Sketches of Our Home Life Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, they detail their wanderings through the wilderness at great length. Elements of these excursions continually recur in their accounts, also figuring prominently in many of their imagined narratives. Though these elements center around the act of hunting, shanties and berrying also recur throughout both the sketches and the narratives.

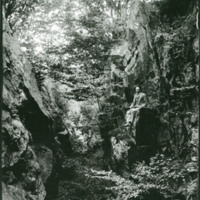

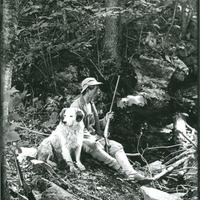

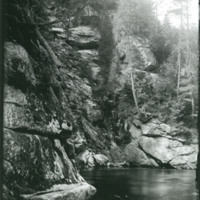

Arthur and Elmner Nelson camping in the Sunapee Mountains, with their hunts' plunder hanging from the top of the kind of "rude shelter" that Captain Charles A.J. Farrar describes (Through the Wilds 292).

A shanty built "of logs" so strong that bullets cannot penetrate them (pg. 9 of Chit-Chat: January 12, 1893).

Shanties:

In Nelson Narratives:

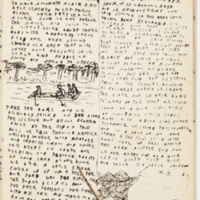

In the January 12th edition of Chit-Chat, the boys describe a fur trader who constructs a shanty out of logs in the “dense wilderness.” Constructed “right in a clump of little spruces and birches and a few other brush,” this shanty – depicted above – is so well disguised that robbers walk right past it. Furthermore, it is so well constructed that when these robbers inadvertently fire at it, the bullets do not “come through,” it being “of logs” of a very protective caliber. At last, it takes a “heavy volley” of gunfire to break down the door, attesting to the merits of this shanty’s sound craftsmanship. Too sound to be true?

(See also: the vivid construction of both a sawmill and a house on Pineapple Hill in the first chapter of American Family Robinson Volume 2)

(See also: The Young Sailor or Deer Lake, for yet another fort in the woods!)

In the Great Outdoors:

The variety of woodland shelters that Captain Charles A.J. Farrar describes in “Through the Wilds: A Record of Sport and Adventure in the Forests of New Hampshire and Maine” (1892) suggests otherwise. As Farrar and his fellow adventurers make their way across the countryside, they make use of substantial lean-to-style “camps,” (315) “rude shelters” “extemporized” with spruce and bare rock, (292) and full-fledged wooden forts that appear to be constructed of bark and lumber (198). Though lake houses also figure prominently in his narrative, it is apparent that New England outdoorsmen of the 1890s construct surprisingly sturdy shelters for themselves on a regular basis.

Alice and Jimmy construct both a sawmill and a house on Pineapple Island (first chapter of American Family Robinson Volume 2).

In Handbooks:

In fact, Daniel C. Beard’s handbook, “Shelters, Shacks, and Shanties,” a do-it-yourself guide that details the process of building such shelters, suggests that this skill was both common and prized among boys. Beard, one of Boy Scouts of America’s original founders, provides his young audience with instructions for building all manner of shanties: from “Indian shacks” and “beaver-mat huts” to “fallen-tree shelters” and the enigmatically titled “scoutmaster.” These constructions are often quite elaborate, boasting “signal-tower[s],” “game lookout[s],” and “observator[ies].” Furthermore, Beard encourages boys to make use of everything from "sawed-lumber" and "birch bark" to "tar paper" and "mountain goose feathers" in construction. Talk about imagination! Though this handbook appeared in 1914, after the period of the Nelson brothers’ book production, it provides a glimpse into the contemporary world of outdoor structures that may have influenced their craft.

In Nelson Sketches:

Thus, while it is certainly impressive that the Nelson brothers show themselves to be such able shanty-builders in their sketches, it is not altogether unprecedented for rugged New England boys to possess such a skill. Nonetheless, their resourcefulness is fascinating, as evident in their firsthand accounts below.

An overnight shelter on the way back from Cousin Alice’s graduation in Milford:

“At last Arthur and I had to leave, we started to go back by the same route that we came on, but at Antrim they told us that it was doubtful if the trains would connect so that we could get through that night, but we tried it taking the train to Contoocook in the afternoon, but we met the train that we should have to take to get home that night, before we reached Contoocook, so we were left to get along as best we might till the next day. After a little talk, we left our bundles at the depot and crossing the road bought a pound of raisins and two dozen crackers at a grocery store, with these we went back into the woods near the village and with one jacknife, we built us a brush hut, thatched over so thick with spruce and hemlock that the mosquitoes did not make out to get in, we tried to sleep that night but did not make out as well as we would have liked to, for though the night was warm it was damp, and we had to move frequently to keep any where near warm. Long before morning came we began to look and wait for daylight” (Sketches of Our Home Life Vol. 1, p. 14).

Straight from the Nelson brother's everyday lives: a striking depiction of a mountainside farm (Five Years in the White Mountains Volume 1, pg. 5).

A Shanty on Big Continent (and a Fraidy Cat Walter!):

“On Big Continent (my island) we built a small, one-roofed shanty in which I hung a small picture and called it both my palace and fort while on round Continent (Elmers) we erected another house of the same pattern as mine; then just in front of this Elmer and Arthur made a ladder on two ash-trees which must have been ten feet high and seemed then a wonderful piece of architecture. Elmer and Arthur once slept over night in their little house and as it was their first experience in camping-out it was probably quite interesting. I intended to sleep there too, but at the last moment my courage gave-'way and I concluded to stay with Papa and Mama” (Sketches of Our Home Life, Vol I, p. 11).

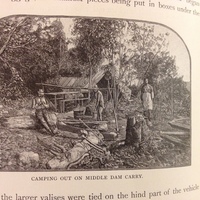

Solid Nelson Constructions (Shanty and Raft) that Withstand the Elements for Years:

“They then followed around the shore until they carne to the head of the pond and also to a little spring which although the water in the pond had a reddish hue is as clear as crystal. From here they struck North and after going a few rods carne to a little bark shanty about twelve feet long and six wide partly covered with leaves and brush which the Nelson Bro's had built two years before to stay in. Here they threw down their packs which had grown terribly heavy in the climb up the mountain and prepaired to make them selves at horne. Elmer got out his camera and took a picture of the camp and boys which would have been a beauty if it had come out all right in the developing. It was then proposed that as it was not dinner time yet some one might hunt up the raft which the Nelson Bros had built on their first camping trip. Arthur voluntered to go and as luck wou!dhave it had to go to the very lower end of the pond after it, and the other boys got nearly devoured by mosquitoes waiting on the shore for him to get back. Lake Solitude seemed to be the horne of the rnuskret, their pathes wound in and out around the rocks and bushes and they already had several houses built on rocks and logs. While the boys were waiting for Arthur they saw a muskret start out from one shore as if intending to swim to the other shore Otho had an idea he could hit him and so fired several shots in his direction with his rifle” (Sketches of Our Home Life, Volume II, p. 4).

Hunting:

Language Across Nelson Narratives and Sketches:

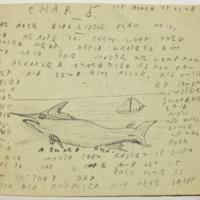

Throughout An Adventure on Red Rover, the Nelson brothers use the same language that they use to describe hunts in their sketches. Phrases such as “he had good luck for he was a good marks man,” (3) and later, “the old bird weighed 100 pounds and the others about 75 pounds,” (14) closely parallel the boys’ descriptions of their day’s plunder in their notes. Furthermore, the call and response yelling that the characters perform is identical to their call and response location technique on a hunt in their High School Notes:

“I followed on down the side of the mountain until I had got nearly to the foot, when I happened to think I had heard nothing of the boys for a long time so I whistled but did not get any answer, then I yelled and fired my gun and still I got no reply. I began to get worried for fear they had lost their way but at last came an answering shout from Walter and Jack who were nearly to the top of the ridge” (High School Notes, p. 14-15).

In the following section from Volume II of their Sketches, the Nelson brothers describe their plunder and estimate their marksmanship in ways that mirror the descriptions that they afford their characters in An Adventure on Red Rover above:

“On our way up the hill Cousin Ernest shot three chipmunks with his pistol and Cousin charles shot one red squirrel and two chipmunks and I intended to shoot most all of them but they got ahead of me. Just as we reached the top of the hill with out seeing a single grey, I saw a red squirrel running along the ground I immediately gave chase and soon had him up a tree. Then I commenced yelling for the other boys to come and shoot him. When they got there Charles told Elmer to take his rifle and shoot it Elmer tried it but missed the first shot and I told Charles that if he would let me take his rifle I'd shoot it but I tried two shots and didn't hit him and Ernest stepped up and shot the squirrel with his pistol and I didn't brag any more” (Sketches of Our Home Life, Volume II, p. 2).

Furthermore, as fond of shooting hedgehogs, squirrels, chipmunks, and other small game as the Nelson brothers were, these experiences provided the imaginary scaffolding for the fictive encounters with everything from hyenas, lions, jaguar, buffalo, and kangaroo – in American Family Robinson Volume II – to panthers (History of Long Continent, pg. 6), bear (Five Years in the White Mountains, pg. 18), and deer (The World, pg. 2). Though these narrative pursuits are fantastic, they possess all of the hallmarks of a Nelson brothers’ hunt in their descriptions, indicating the substantial degree to which their intimacy with hunting practice informed their literary play. Rounding out the spectrum of narrative pursuits, mundane aspects of hunting feature in the boys’ books as well, such as the unfruitful checking of traps and the prevalence of mere squirrels as objects of the hunt in Wonders of the Forest.

Hunting and Rural Childhoods in the 19th Century: Though the image of miniscule Ernest raising a pistol and felling wild animals may suggest to the contemporary reader that the Nelson brothers were unique in “starting young” with regard to hunting, the boys were not alone. In her article, “The Pleasures of Youth,” Priscilla Ferguson Clement offers the following characterization of rural boyhood in the nineteenth century: “Farm boys kept busy working except in the winter months, when they attended school and there played sports with other boys, hunted rattlesnakes, and copied adult farm chores by branding gophers with little irons…” (Clement 160). This is not to depreciate the value of the tactile knowledge that hunting dangerous animals, engaging in tasks of farm labor, and helping out with the family business of sugaring afforded the Nelson brothers’ narratives, but rather to situate their outdoor activities within a cultural milieu that very much encouraged such behaviors.

Berrying:

Another real-life pursuit that figures heavily in the Nelson brothers’ narratives is berrying. In American Family Robinson Volume II, the author(s) go into great detail about the process of knocking peaches out of trees and cracking open coconuts. Five Years in the White Mountains devotes an entire chapter to “Beachnutting and Blueberrying” – not to mention the farm catalogues, which go into extensive detail about the respective taste, heartiness, and texture of a literal cornucopia of fruits.

According to their journals, berrying also proved a cherished activity in their everyday lives. The following passages capture the lightheartedness of this quaint New England activity, displaying the great fondness that the boys had both for the fruits and the adventures entailed in their pursuit:

“This farm had a large quantity of raspberries, and blackberries, and a few blueberries; these I much enjoyed picking. They also brought in a little spending money. This place was close to a brook which furnished much pleasure to the boys making a fine place in which to paddle barefoot, or sail boats. These last it was Walters great delight to go across the road into papa's shop and make. The pastures furnished delightful places for playing Indian.” (Sketches of our Home Life Volume 1, p. 2).

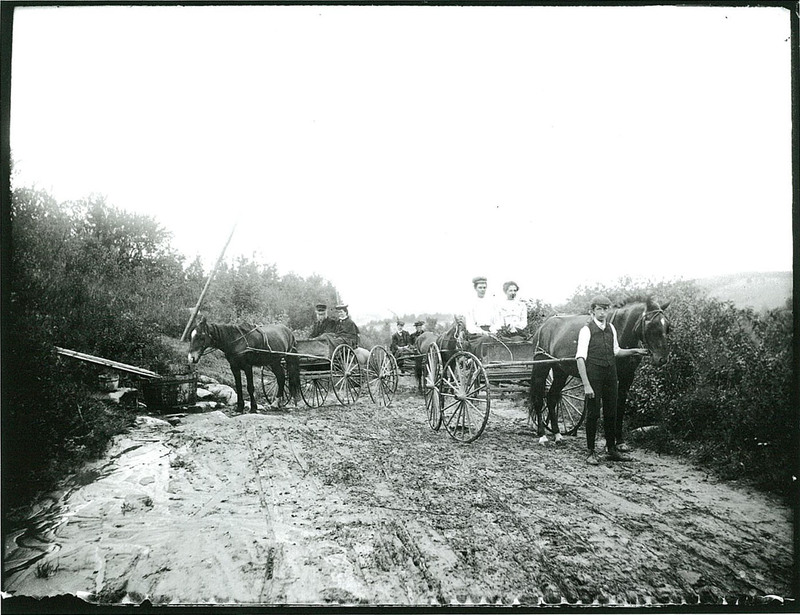

“As black berries were very thick along the road we got an empty pail out of our wagon and began picking black-berries to go with our dinner while we waited for the rest of the party. As soon as aunt Miras folks caught up we started on they had two teams Henry, Aunt Etta, Freddie Upton & Jennie in one and Arthur, Aunt Viola, and Aunt Mira in the other. As we were driving by or rather through a patch of black berry bushes, where the black berries were very thick I spoke to mama and said look at those big black berries, and as I spoke I pointed with my hand and nearly hit an old man who was picking black berries in the patch I had not noticed before” (Sketches of Our Home Life Volume 1, p. 28).