Artists' Hands

Although the production of the brother’s histories, stories, catalogues, and gazetteers was a collaborative endeavor, in many cases the author and artist of individual books can be identified, and the hands of Elmer, Arthur, and Walter thus can be recognized.

Elmer

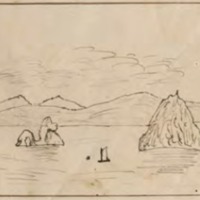

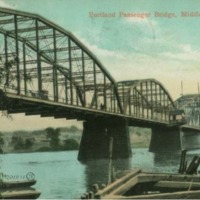

Elmer, the eldest of the three brothers, develops a style that is particularly well attuned to the landscape. Thus, in an early illustration of a boat Elmer shows care in depicting the boat accurately, though the horizon line is wrong and his figures are awkward. In later books Elmer continues to pose rather awkward figures in a landscape that is quite delicately depicted.

An early boat by Elmer American Family Robinso[n]

An early boat by Elmer American Family Robinso[n]

"Pontacook Falls," Forest of Dixville

"We tried fishing" Forest of Dixville

Arthur

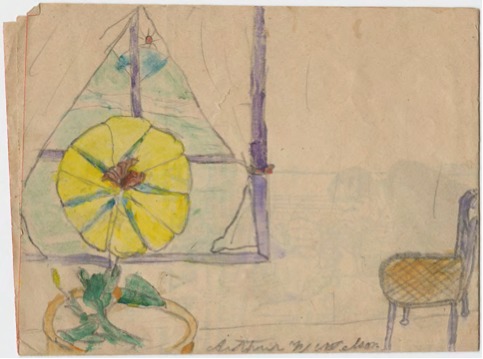

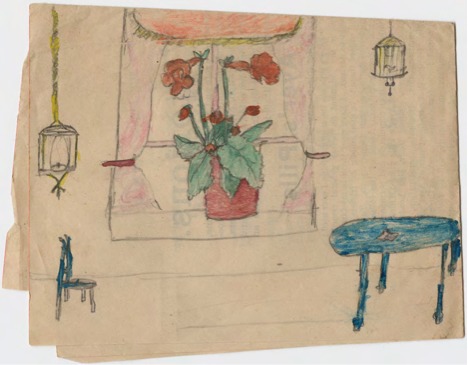

With Elmer setting an example, the second-oldest Nelson brother, Arthur, develops into an exceptional artist. Arthur’s skills are clearly seen in a series of watercolors of flowers, one of which he has signed. The signed watercolor is on the backside of a handbill for Ayer’s Pills and Ayer’s Sarsaparilla that was issued by Farr and Tandy, Goshen, Mill Village, P.O., N. H. This handbill is illustrated with an etching that also appears on Ayer’s advertisements of the 1890s and 1891s, and it is thus unlikely that the watercolors were made much after 1893 or 1894, when Arthur was 13 or 14 years old.

If Arthur’s oddly angled furniture has an unintentionally Matisse-like modern feel to it, his sensitivity to placing the flowers within the window frames creates appealing compositions.

This painting was done on the verso of a flyer for Ayer's pills

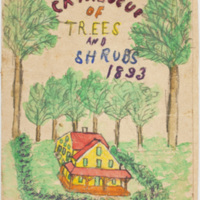

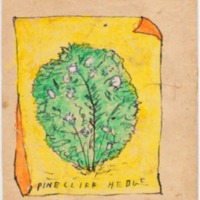

We can identify Arthur’s watercolor style in a number of illustrations in the collection of the boy’s books. The house on the cover of Littles Catalogue of Trees and Shrubs 1893 and the trompe l’oeil advertisement for a “Pinecliff Hedge” uses the same yellow and orange gouache employed on the flower in the signed drawing.

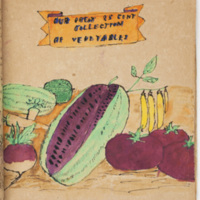

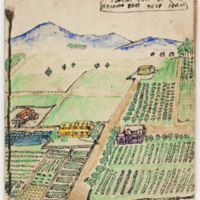

The same careful employment of gouache can be seen on the bird-eye “Partial view of the Nelson Bros Seed Farm” on the cover of Nelson Bros Novelties and in the “Our Greatest 25 Cent Collection of Vegetables,” with its elaborate banner.

and the Nelson Brothers' Novelties seed catalogue

As “the worlds historian” for the three brothers’ imaginary landscape, Arthur was the main writer and illustrator of many of their books, often using thinly-disguised pseudonyms, most frequently the Long Continent hero, “Walter J. Little.” In Arthur’s early work, such as Adventure on the Scud (by AW Nelson) and An Adventure on Red Rover (by Arthur Little), Elmer’s influence can be seen in the attention given to the boat and in the awkwardness of the figures.

Although Arthur Little is described in An Adventure on Red Rover as “a common size boy of fourteen years not so large as Otho [Strong] but more muscular than he,” and fellow coal miner Walter Allen is said to be “about twelve years of age.” It would appear, however, judging by the style of his work, that Arthur Nelson wrote this adventure story when he was younger than 14, using book-making to inflate his age as well as his muscles.

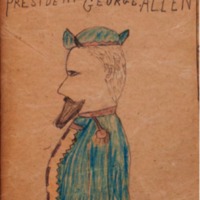

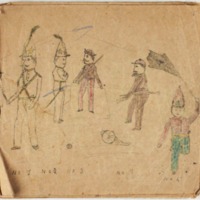

One of the recurrent themes in Arthur’s illustrations is the military portrait. We can see a progression from the earliest, awkward profile drawings found in Eathan F. Allen and his Family and in the Complete History of Big Continent, to the more refined portraits of William J. Little and Bert S. Green that were pasted into the History of Long Continent by “AW Nelson”—a book that, judging from the primitiveness of the other illustrations, was apparently originally made by a much younger Arthur.

While the pasted-in portraits of William J. Little and Bert S. Green have skillfully rendered facial features, the awkwardness of their scribbled, pointy beards suggest that Arthur drew these before he himself had first-hand experience with whiskers.

Miliary portraits from Eathan F. Allen and his Family

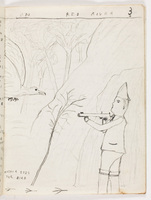

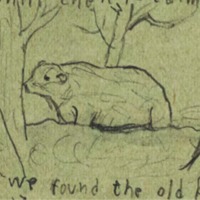

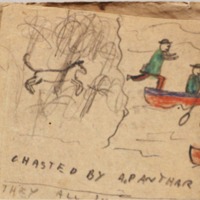

"Chasted by a panthar" in History of Long Continent

into the History of Long Continent

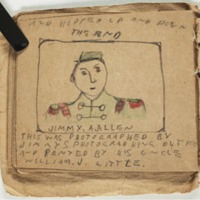

Another, slightly cruder, rendition of Eathan F. Allen, was also pasted into “Popies Cruse,” a work apparently made by a young Walter. Each drawing in this book occupies a single page, and, on the last page, a portrait of Jimmy A. Allen is labeled: “This was photographed by Jimmys Photographic Outfit and panted [sic] by his uncle William J. Little.”

One other illustration in “The Popies Cruse”—a dramatically posed Jimmy watching the battle “with a steady eye”—may also be the work of Arthur; it was certainly not made by the same hand as the other crude depictions in the book, such as “The battle is won.”

both in The Popies Cruse

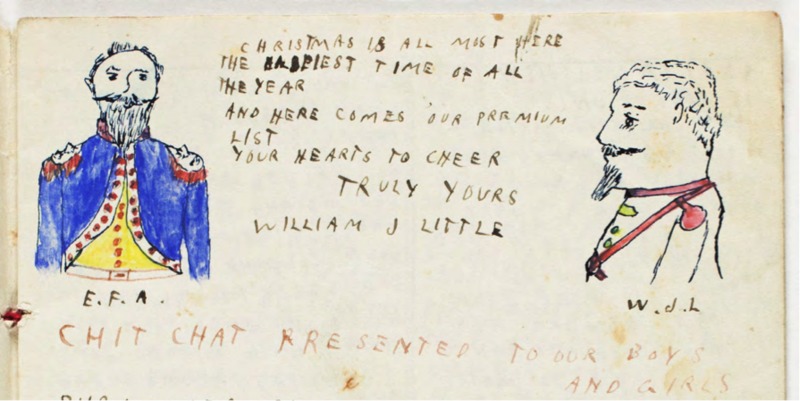

Among Arthur’s most successful portraits are a pair adorning the inside cover of the February, 1893 edition of “Chit-Chat.” The raised eyebrows of E.F.A. looking across to a properly-bearded W. J. L makes for a charming scene.

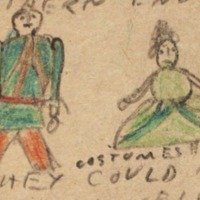

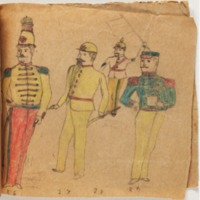

Just as with Popies Cruse, there appears to be two different hands at work in the thirty-two figures illustrating Military Uniforms. The first nine are crudely drawn, while the remainder are much more carefully posed. The coloring technique of these latter, more successful, drawings matches what we have already identified as Arthur’s hand.

The inspiration for the elaborate collection of uniforms the Nelson brothers depicted is undoubtedly illustrations that they saw in such popular publications as Youth Companion. We should note, however, that the boys were not merely copying what they saw in print; they were, rather, incorporating these models into their own imaginary world.

Arthur’s interest in depicting the military was especially directed to all matters naval. The coloration and style of the delightful books of Flags allows us to assign to Arthur’s hand these banners from the boy’s imaginary island continents.

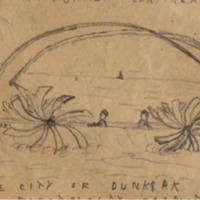

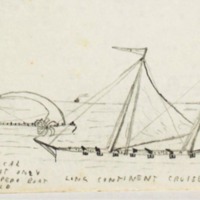

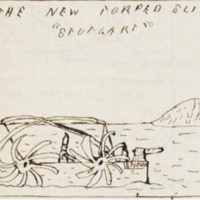

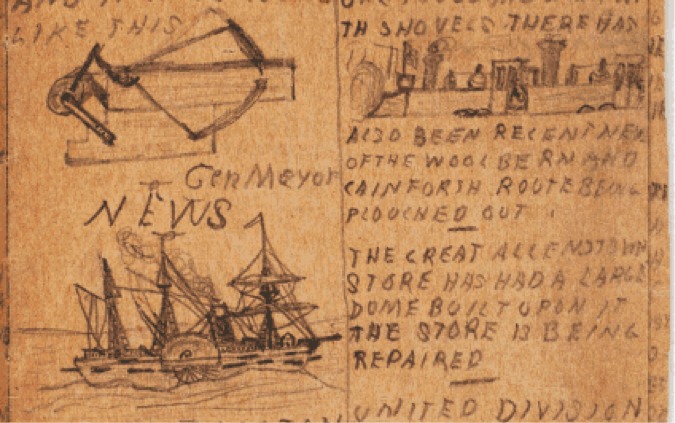

The collection of Nelson Family Juvenilia abound in ship illustrations, for which, like the military uniforms, printed engravings undoubtedly served as models. Nonetheless, the Nelson boy’s creativity brought these templates into the iconography of their imagined world, with seas plowed by all sorts of vessels, powered by sail, steam, and even electricity. Arthur’s fanciful electric torpedo boat, the Dunkirk, appears in the February 1893 Chit-Chat and is more fully described in the Thirty Days War. Two years later, Arthur creates a second electric torpedo boat, the Stuttgart, which appears in the Jan. 29, 1895 edition of War News and in The Weekly Telegram of Jan. 23 1895. These paddle-wheeled boats, could, as Arthur notes, provide only short-distance harbor defense because of their limited range.

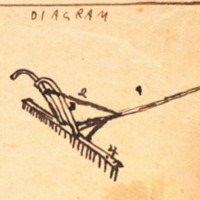

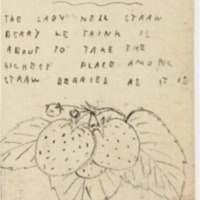

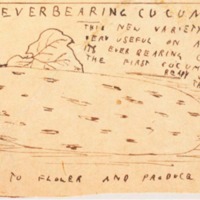

All of the Nelson brothers show signs of having received instruction in technical drawing, as we can see with the fifteen-year-old Arthur’s fanciful “The Great BC Telescope” in the January 1895 issue of War News or in his carefully rendered “The New Derry Harrow” which appears in the April 1894 issue of The Intellectual Farmer. Arthur’s technical skill with pen and ink can also be seen in the careful depictions of agricultural produce, such as “The Lady Nell Strawberry” and the “New Everbearing Cucumber.”

The Great B.C. Telescope in War News

he Derry Harrow in The Intellectual Farmer

In Sunny Shore Record (by "WJL")

and The Intellectual Farmer, April

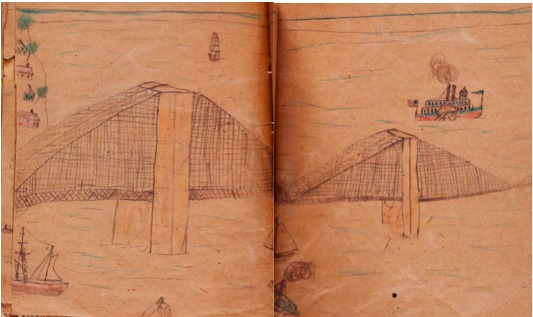

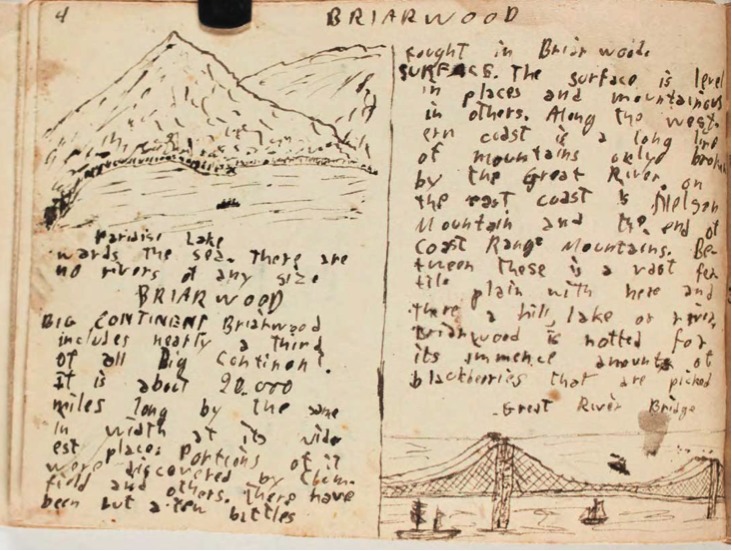

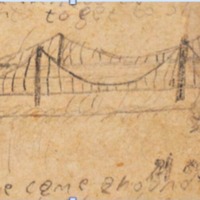

Suspension bridge spread in the Complete History of Big Continent

and a similar bridge drawn years later for the Gazetter of the World

The Complete History of Big Continent—whose crude portraits of George Allen and Ethan F. Allen identify the book’s illustrator as a young Arthur—has an unusual two-page illustration of the bridge over Great River on Big Continent, which is described as: “so long that any one could not see more than half the length of the bridge it was the largest in the world the Big Continent people were very proud of it it was five hundred and fifty miles long.” Arthur’s drawing looks like it might have been inspired by an engraving of the Brooklyn Bridge. The motif of a suspension bridge with boats reappears in the Gazetter of the World, whose skillfully drawn illustrations place it as one of the last books produced by the Nelson brothers.

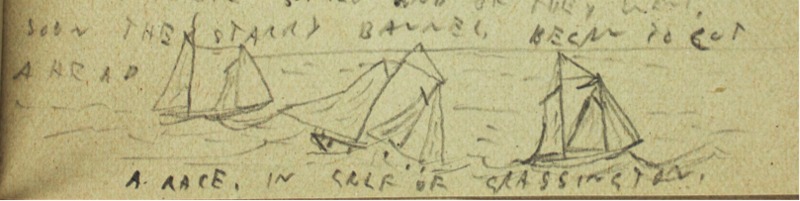

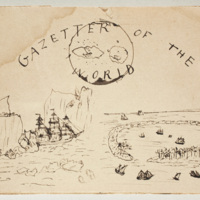

On the title page of Gazetter of the World are scenes of an elaborately detailed three-masted schooner emerging from icebergs and of a fleet of ships sailing around an atoll. Here we can observe a sure hand that was comfortable with depicting sailing vessels—something that Arthurs clearly demonstrates with his little vignette of tossing sailboats that appears in “Rough-it Club.”

Rough It Club by William Little

boats on the cover of Gazetter of the World

One of the remarkable features of Gazetter of the World are the detailed drawings of large urban buildings, such as “W.M. Strong’s Store” in Mapleton or “Nelsons Seed House, Allentown.” Such buildings were not a part of the Goshen brother’s rural landscape, and despite occasional travel to Worcester or Boston Arthur was surely relying on engravings he saw in print when he created these drawings for the Gazetter. Here, again, it should be noted that, far from merely copying these adult models, the Nelson brothers expropriated them to use in a world of their own creation

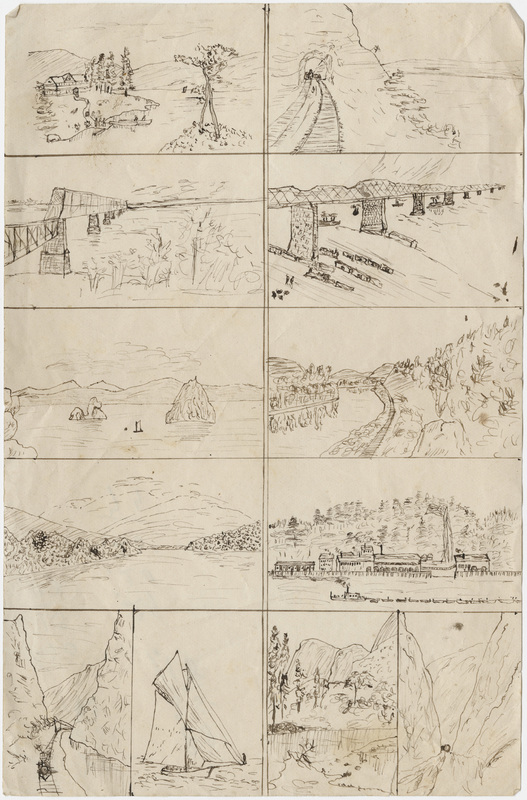

Impressive technical drawing and scenic vision of the single sheet "Twelve Scenes"

By far the most impressive artistic work in the collection of the Nelson Family Juvenilia is “Twelve Scenes”—twelve ink landscapes drawn on a loose sheet of paper. A double line divides the center of the paper, and four pairs of horizontal scenes are placed above a row of four vertical scenes. Comparing these scenes of bridges, sailboats, trains, rivers, lakes, and mountains to what is found in Arthur’s earlier book illustrations suggests that “Twelve Scenes” is the work of a more mature Arthur, drawn after he and Elmer had graduated from making picture books to photography.

The way that the “Twelve Scenes” sheet was prepared to receive the horizontal and vertical drawings is analogous to how the Nelson brothers left blank spaces in their book narratives, into which they would later add illustrations. The ink landscapes on the unfolded sheet, however, were not made to illustrate a narrative, and they appear not to have been drawn en plein air. As with the military uniforms, ships, and buildings depicted in the Nelson brothers’ books, it is quite likely that the inspiration for at least some of these twelve scenes came from printed material. Nonetheless, given the fact that we had already seen Arthur expropriate adult publications in the books he illustrated when he was thirteen- to fifteen-years old, it seems reasonable to assume that these twelve ink drawings depict landscapes imagined by an Arthur in his late teens.

earlier work like the hills in Gazetter of the World

The idea that Arthur might have drawn “Twelve Scenes” when he was seventeen or eighteen is supported by the photographs that he and his brother took in 1897 and 1898. Although the majority of the Nelson brothers’ photographs, now housed in the Goshen NH Historical Society are portraits and group shots (the brothers were trying to sell their photographs, after all), there are a number of landscape photos which match the tone and composition of the ink drawings in “Twelve Scenes.”

Walter

As the third brother, Walter was only thirteen when the production of the hand-made books came to an end in 1895, and we have only a handful of illustrations that we can assign to his hand, such as the crude drawings noted in Popies Cruse. From the Mountain News (Feb. 5) which was “Published by WR Nelson Greenville Willows,” we can see that Walter demonstrates the same interest in naval scenes and the same skill in technical drawing that is evident in the work of his elder brother, Arthur.

As the Nelson Brothers Juvenilia apparently does not contain any work of Walter after 1895, we simply do not know if he went on to become as accomplished an artist as Arthur.

Walter's nautical and technical drawings in the Mountain News

In The Western World by “WR Nelson,” Walter has depicted a bridge reminiscent of Arthur’s early work