Adventure

Defining "Adventure" in the late 1800s

Growing up in the late 19th century certainly played a role in shaping the lives of the Nelson brothers. As constant students of their surrounding world, the boys were heavily influenced by prevalent literature and applied literary techniques gained from other stories into their own work. Successful children’s writers used a literary style which focused on adventure in the late 19th century, which heightened the boys’ awareness of the adventure genre and inspired them to recreate these same concepts within their imaginary and realistic worlds. There is a clear attempt for the characters in the Nelson brothers’ stories to achieve their goals after conquering some sort of conflict within the respective plots.

Elmer Nelson describes his own collection of literature and notes “One of the classes of books which interests me most is adventure stories,” especially “those located in distant places”(My Library). He continues and writes “One of the most interesting books of this class which I have read is ‘Michael Strogoff’ by Jules Verne.”(My Library). Jules Verne, as many may know, is one of the most iconic authors of adventure and science fiction, and was also a famous French playwright, novelist, and poet with notable titles such as Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869), and Around the World in 80 Days (1873). Most of his works were later translated for English distribution and eventually made it into the hands of young children like Elmer Nelson.

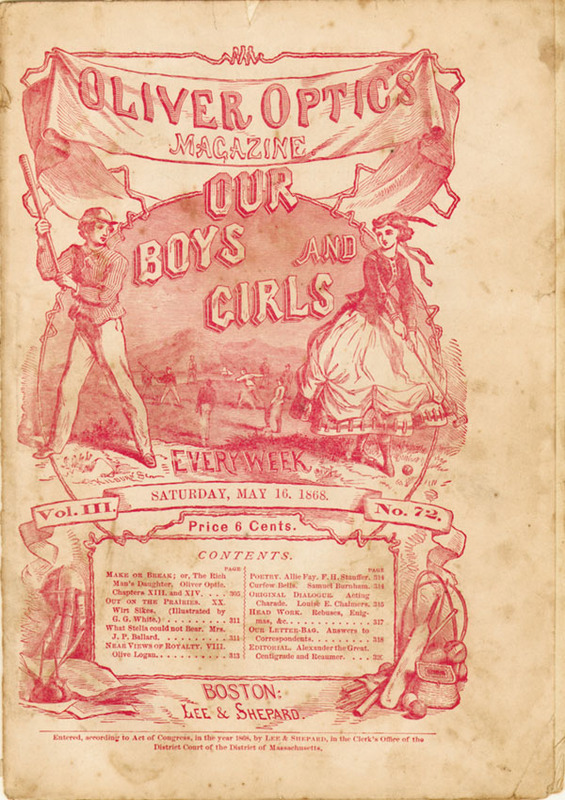

Cover of Oliver Optic's, "Our Boys and Girls." Notice any similarities with Chit Chat and other periodicals?

Another famous writer that was an integral part of Elmer’s library and development of his interest in the adventure genre was William Taylor Adams, better known by his pen name “Oliver Optic.” Elmer notes, “I also have one of Oliver Optics books. Fighting for the Right which is located in the south at the time of the Civil War,” and continues to discuss his passion for books about “travel and history,” writing that he “always had a desire to travel and see something of the world” (My Library). Oliver Optic was said to of had “the ability of writing stories that were so natural and everyday in their setting that his boy readers unconsciously became in imagination the heroes themselves." This is clearly something that the Nelson brothers strive for in writing their own stories, taking on alter egos and assuming the hero position. The Nelsons often include three brothers in adventure tales, slightly altering the names, allowing the reader to presume that the brothers wished to include a piece of themselves in their fictitious tales.

Both Oliver Optic and Jules Verne mastered the art of the adventure fiction tale and provided an example for the boys to model their own stories after. Oliver Optic kept his storylines clean and moral, and never had the reader feel sympathy for the villain—as do many of Nelson brothers’ works. Both Optic and Verne had travelled throughout European countries, gaining knowledge and experience to incorportate into their fantastical stories. This, as previously noted, was the very dream of young Elmer Nelson. Stuck within the confines of the rural town of Goshen, NH, Elmer and his brothers were instead left to imagine their own world inspired by the adventurous tales written by authors who had travelled the world. Instead of travelling the world themselves, the brothers created an imaginary world that their characters travel within and where the opportunities for adventure were endless.

The Beginning

The Nelson brothers’ efforts to write stories that fell within the adventure genre began at a young age. One example of a rudimentary adventure story produced by Elmer Nelson is Jim’s Cruise. Jim's Cruise is a short story about a fourteen-year-old boy who boards a ship and embarks on an adventure that takes many unexpected turns. The adventure begins with Jim having the “chance to go on board of a ship bound to a small city on Fork River over on Round Island. He thought it would be great fun to be a sailor. He didn't know about sailing so very much but he went on and the vessel started the third after”(Jim’s Cruise).

Elmer includes exciting plot turns within his story, but fails to expand on any of the events he presents within the plotline. In Jim’s Cruise, Jim does not know about sailing but goes anyway. He feels sick upon walking onto the boat, but nothing bad ends up happening as a result. At first, Jim cannot reach the eagles on the island, but all of a sudden, he can. Even though a storm disables the boat beyond repair, the crew is somehow able to sail back to land. Additionally, during the storm, several men are thrown overboard. Despite all of the hardships, Elmer concludes the story by saying that Jimmy enjoyed the trip. The jumpy writing style is representative of Elmer’s youth, but also suggests that this is one of his initial attempts at writing an adventure story. He understands that conflicts are involved in an adventure, but makes them disappear before resolving these issues.

Adventures at Home

As the Nelson brothers continued to develop as young authors of adventure stories, they decided to look no further than home and created adventures out of realistic experiences in their surrounding environment. The first chapter of Seven Days in the Country introduces the characters Dick, Fred, and Franz—brothers that enjoy playing in the outdoors from the "milk-room roof" to "Hedgehog Ledge." The brothers in this story seem to mirror the lives of the Nelson brothers and how they educated themselves through adventures around the house. The author introduces the characters and writes “Dick the oldest one was fourteen then Fred who was twelve and Franz nine years old then came the baby eight months old”(Seven Years in the Country, Ch. 1). The same sentence can be rewritten to fit the exact mold of the Nelson brothers, with Elmer as the oldest, then Arthur, Walter, and eventually the baby Ernest. Here, one notices the Nelson brothers’ attempt to design stories inspired by their own experiences or recreate circumstances within fiction that allows them to embark on their own desired adventures. The fourth chapter of Seven Days in the Country details Fred and Dick's attempt to corral a stray calf that escaped from the pasture. Even though Dick hurts himself, he returns to finish clipping the lawn before returning back home to write. These events may have very well happened to the Nelson brothers, but they create a narrative that involves different characters, which eliminates the restriction of the actual events and allows the boys to use their imagination. The boys manage to create an adventure within the limits of everyday life and further the development of their adventure story writing capabilities.

Similarly, in Wonders of the Forest, three brothers, presumably the Nelsons, hunt for squirrels and pretend to ride a horse after discovering a tree that had a "limb for a tale [tail] and limbs branched down for [the horse's] feet." This story about both realistic and imaginative discovery in the nearby woods illustrates an expansion of the Nelson brothers’ personal adventures in the surrounding area, as well as another attempt to convey their own adventurous experiences in a story format.

Direct Attempts at Writing Adventure Stories

There are a couple instances where the Nelson brothers include the word “Adventure” in the story’s title, defining their story’s intended genre so that readers already know what to expect prior to reading. Their direct attempt to write an adventure story shows their continued enthusiasm towards creating their own personal and imaginary adventures around Goshen. Some of the Nelson brothers’ stories represent events that actually happened and their conscious use of “adventure” in their stories’ titles is an example of the boys placing their own lives within that genre.

One example of the boys transcribing real-life adventures into stories appears in Adventures on the Scud, a story written by Arthur Nelson that describes his and his brother's struggle maintaining their ship against the melting ice in the spring. After falling trees hit their boat, the boys are left with no other choice but to repair their ship with some helpful donations from the townspeople. This story actually happened and does not include imaginary characters or continents, yet Arthur is still able to frame an adventure story within the imaginative limits of reality—creating conflicts and eventually overcoming said obstacles before the conclusion of the story.

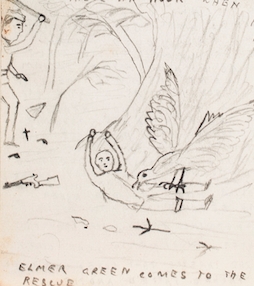

An Adventure on Red Rover illustration

There are also certain stories that incorporate imaginary characters with a realistic flair. An Adventure on Red Rover is an illustrated 12-page story by William J. Little about an attack by three giant birds on Walter Allen, age 12 and Otho Strong, age 14. The boys are eventually rescued by Arthur Little, age 14 and aided by Elmer Green (no age given). The reader cannot help but notice the Nelson family names incorporated into the first names of each character: Walter, Arthur, Elmer, and their cousin Otho. Even though this adventure takes place in their imaginary world, the brothers are inserting a piece of their own lives into the story and vicariously experiencing the thrilling action themselves.

Discovering their Voice as Adventure Writers

After writing many stories, the Nelson brothers began to find their voice as adventure writers and wrote more mature stories with a definitive sense of direction. Their narratives revolved around the same topics, but the boys became interested in consciousness and included what their characters were feeling and thinking, not just what happened to them. In Forests of Dixville, the narrator, Jack, and their dog Rover explore the White Mountains. The duo stops in Gorham, NH and the narrative discusses peaks such as Madison, Adams, Monroe, and Washington—all realistic places that exists as a part of the White Mountains’ “Presidential Peaks.” It is difficult to predict whom the narrator is and whether or not the characters are imaginary, but the setting of this story is certainly realistic—representing another instance where the Nelsons blend their imagination with reality.

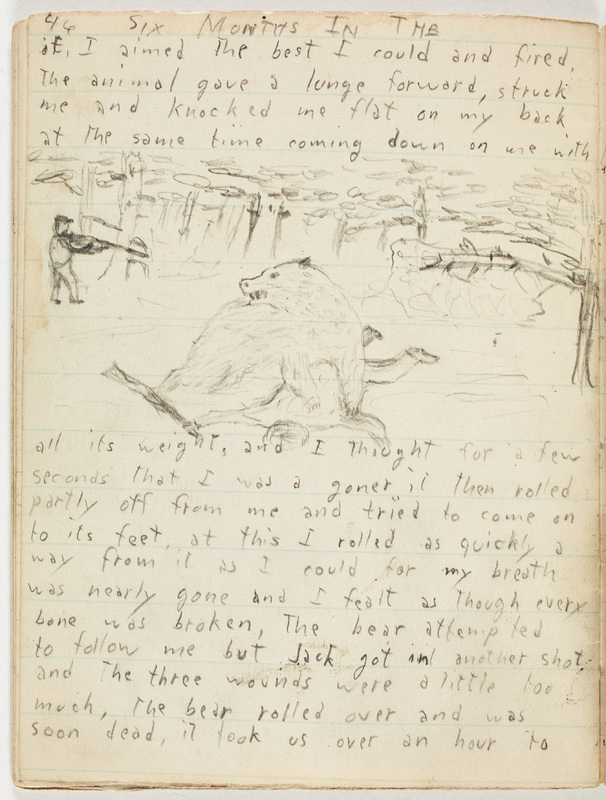

The stories become more entertaining when the boys begin to write with vivid detail. The author’s adventure writing capabilities shine as the suspense builds in the following passage:

“I started to step forward and pick it up I was startled to see a large, black shaggy animal rise from among a clump of hemlocks and start toward the partridge, then as it turned and faced me with a low growl I realized that I was confronted by a black bear and as I afterward found out a large one too, as this thought flashed into my mind, I put my hand to my side for a heavily loaded shell, but as I done so the thought came, ‘There I have left my belt at camp and have only two common loaded shells with me.’ The bear dropped down on all fours again and moved toward me with a shuffling gait, keeping my eyes on the bear I partly turned and called to Jack to bring his gun and my belt. I then backed off in the direction of the camp with my eyes on the bear, it was but a few seconds before I heard Jack come running through the woods though it had seemed a good while, just as I heard Jack speak close to me, I struck my heel against a fallen log and over I went, I did not lay in that position long and when I come to my feet jack stood beside me with his gun to his shoulder and not two rods of was the bear still advancing, as I arose I slid a shell out of the belt that Jack had brought and into my gun as I was doing so there came a report and the bear staggered but did not fall, then he came at us with a speed that nearly took our breath away and by the time I could bring my gun to my shoulder the bear was nearly to muzzle of it, I aimed the best I could and fired. The animal gave a lunge forward, struck me and knocked me flat on my back at the same time coming down on me with all its weight, and I thought for a few seconds that I was a goner. It then rolled partly off from me and tried to come on to its feet, at this I rolled as quickly away from it as I could for my breath was nearly gone and I fealt as though every bone was broken. The bear attempted to follow me but Jack got in another shot and the three wounds were a little too much (Forests of Dixville).”

The Nelson brothers were first inspired by reading the works of successful children’s adventure-fiction writers, such as Oliver Optic and Jules Verne, and eventually were capable to create their own adventure stories dealing with their imaginary and realistic lives. As with anything, more practice produces a better result, and the boys’ consistent story writing habits helped strengthen their narrative voices over the course of their young childhood—especially when it came to crafting a compelling adventure tale.