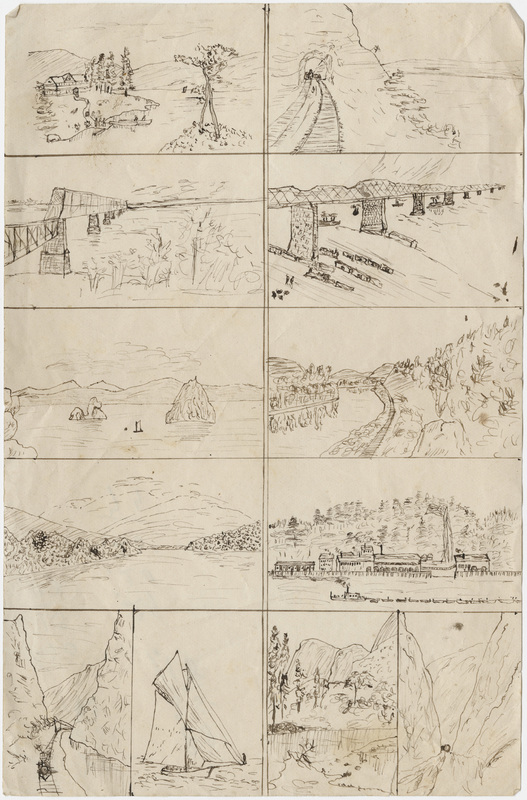

Illustrations

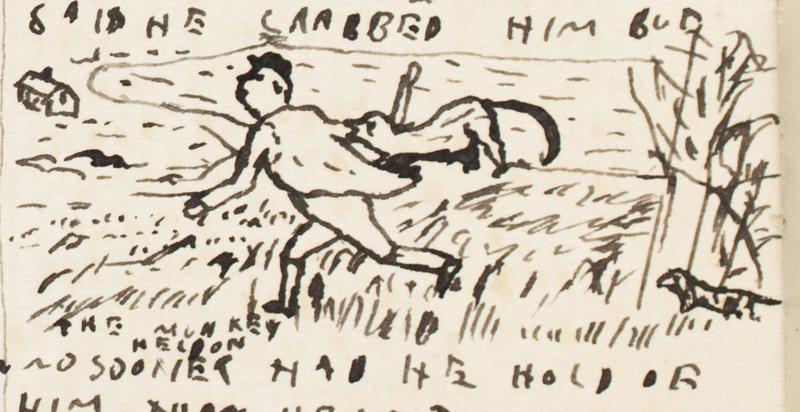

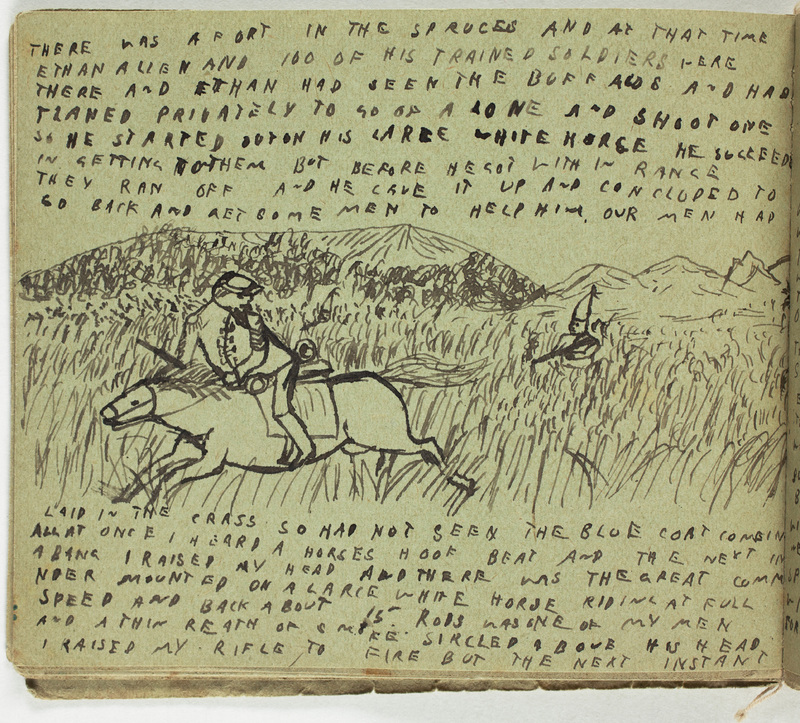

“Twelve scenes” in the Nelson Brothers Juvenilia. These pen-and-ink sketches, executed on a single sheet of paper, are apparently the latest work by Arthur Nelson in the collection, and these evocative scenes are an extension of the imaginary world created by the three Nelson brothers.

Art Pedagogy

In his 1896 Sketches of Home Life, vol. 2, a 16-year old Arthur describes a hunting trip to Vermont, during which he looks back on the mountains of New Hampshire and muses: “I can hardly explain to you how beautiful the old State looked, only it was a great many times as grand as any picture I ever drew up in school.”

While there is no record of the exact art education curriculum Arthur and his brothers may have studied in the Goshen and Newport schools they attended, we can be sure that it followed the general outlines of what then called “Manual Training.” After the adoption of the groundbreaking Massachusetts Drawing Act of 1870, which mandated drawing instruction in all of the state’s public schools, the next two decades saw art education become an established part of school curricula throughout the country. Fueled by a desire to improve the moral lives of students as well as to prepare them for adulthood in an industrial age, progressives saw manual training as a way to instill an appreciation for the arts as well to teach the practical skills of technical drawing—which for boys meant being able to draw plans for machinery, and for girls being able to create sewing patterns.

In a paper on “Education as Affected by Manual Training” presented at the 1893 National Education Association, Henry M. Leipziger concludes:

Under a system of training in which manual training plays a proper part, the wealth of our land will be vastly increased, the perceptive faculties will be developed, the æsthetic side will be nurtured, the distinction between the manual worker and the brain worker will be obliterated, and each human being, having learned to think, observe, and act for himself, will enjoy his own life and not be the echo of another, and then will be realized the dream of Emerson:

“His tongue was framed to music,

And his hand was armed with skill,

His face was the mould of beauty,

And his heart the throne of will.”

The Nelson brothers—embodiments of this Emersonian independence—certainly did have hands armed with skill. Growing up among the fields and forests of rural New Hampshire, they were attuned to the natural world, and would have drunk up lessons in nature drawing, another popular form of art education in the 1890s (Stankiewicz, 2001).

From their earliest, childish, drawings to their more developed sketches, Elmer, Arthur, and Walter Nelson adapted their school-taught lessons for the illustrations they made about their imaginary worlds. Along the way, they helped each other to develop a coherent style and a consistent set of conventions for their book illustrations.

The graciousness of “Twelve Scenes” also speaks to developed sensitivity toward art than one might not have expected in this rural family. In High School Notes, a twenty-two-year old Elmer records a trip he and his brothers made to Worchester and Boston in November, 1900. In Worchester, their Aunt Sadie took them to the Art Museum, where Elmer says “. . . In the other room were some fine paintings, some of them looked dauby near to but at a distance their beauty was apparent. the picture which most interested us and held our gaze was one of carrier pigeons being liberated at sea by naval officers. The water almost seemed to ebb and flow it was so real. Two moonlight scenes were fine. There were also several pictures of cattle and sheep feeding.“

Nelson Brothers as Illustrators

In his 1899 school essay, “My Library,”—which was corrected by his teacher—Elmer says that Tom Brown’s Schooldays and Tom Brown at Oxford are “books which are interesting to any schoolboy,” adding “Many of Tom’s experiences are our own.” These Tom Brown stories, written in 1857 and 1861, are set in English schools, and are illustrated by framed etchings dispersed throughout the chapters. The Victorian style of the Tom Brown etching bears little resemblance to the Nelson brother’s artwork, although the boys’ books are similarly illustrated with labeled drawings scattered throughout the text.

The boys left blank spaces on the pages where they wrote their narratives, coming back after writing to put in the drawing, as can be seen on the unfinished “Seven Days in the Country."

Given this write-draw-write technique of composition, it is of little surprise that the majority of the illustrations in the Nelson brothers’ books demonstrate what Joseph Schwartz (1982) calls congruency—that is, that they closely follow the narrative with little elaboration.

The close relation between illustration and text can be seen in many of the books the boys made:

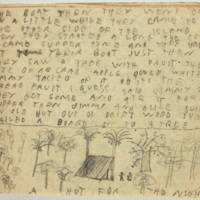

drawing of a hut in American Family Robinso[n]

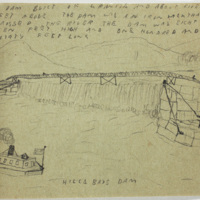

Drawing the Hillsbrys Dam from Different Stories

In American Family Robinso[n] Elmer Nelson calls attention to the drawing in his text: "Jimmy and Alice built an old hut out of drift wood they nailed a board on to a tree then they nailed boards up and down as you see in the picture then they got a big plank for the door then they went in and layed down and went to sleep"

In his 1982 study of illustrations in children’s literature, Schwartz notes that images serve as socializing tools, and that, in our technological society, special focus is put on gadgets and machinery. As the boys faced each decision of precisely what to draw in a given reserved space, they frequently chose the mechanical. A typical example of this trend can be found in Different Stories where both the writing and the drawing pay much attention to technical detail: "we steamed up the river to Hillsbrys Dam hear was a small summer resort with a little store Hillsbrys Dam was a dam built of granite and about five feet above the dam was an iron wall that crossed the river the dam was eighteen feet high and one hundred and thirty feet long."

A detail from the January 1893 issue of the brother's periodical Chit Chat

Cavalry illustration from Thirty Days War

For the most part, the Nelson brothers were primarily interested in spinning rambling tales, and the illustrations they added to their books were of secondary importance to the narrative. Still, they clearly enjoyed turning their pencils and pens to these illustrations, and one can appreciate their developing aesthetic and technical skills in creating vignettes that dynamically bring us into their imaginary worlds.

SOURCES

Charles A. Bennett (New York College for the Training of Teachers), “Manual Training from the Kindergarten to the High School,” Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the National Education Association of the United States, Washington, DC, 1893, pp. 449 – 455.

Henry M. Leipziger, “Education as Affected by Manual Training,” volume of the Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the National Education Association of the United States, 1892, pp. 439 – 443.

James McCalister (Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry), “Art Education in the Public Schools, Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the National Education Association of the United States, Washington, DC, 1891, pp. 456 – 466.

Joseph H. Schwartz, Ways of the Illustrator: Visual Communication in Children’s Literature, American Library Association, 1982.

Mary Stankiewicz, 2001, Roots of Art Education Practice, Davis Publication.