War

Nelson's At War

War was a prevelent theme in the games the Nelson brothers played and the books and stories that they wrote when they were young. Though their little books seem to have been written earlier, the brothers did have some exposure to an actual war when the United States entered the Spanish American War. The boys explain that the town of Goshen did not seem very patriotic before the destruction of the Maine in February 1898, but "the news that a terrible flotilla of eight torpedo boats and torpedo boat destroyers was on its way from Spain to the United States filled the country with alarm" wrecking havoc even in as rural and isolated a town as Goshen (Sketches of Our Home Life, Vol.2 p. 15). The victory of Commodore George Dewey replaced the town people's anxiety with confidence. Their experience of reading and writing about the Spanish American War forced the Nelson brothers to think about the realities of war, not just to enjoy imaginary battles. Although other boys in the town enlisted the Nelson brothers did not. In the violence of their hunting stories they wrote gleefully about shooting guns and killing animals--and they wrote from real experience--in their war stories they did not have that actual experience and they seem unsure whether or not they want it:

As my writing closes, August lOth, the terms of peace have been given to Spain and it is rumored she has virtually accepted them. So the end of the war seems already in sight - the shortest and most decisive war the United States has ever waged - and we hardly know whether we wish we had enlisted or not.

-Walter R. Nelson

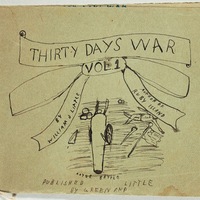

Thirty Days War

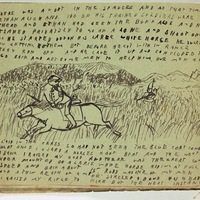

The Nelson brother’s lighthearted outlook depicted in Thirty Days War doesn't get rid of the grim calamities of war. Their wispy and playful style, especially in the joking tone of the narrator coupled with direct descriptions and observations gives a realistic sense of the difficulties of war and yet makes it seem enjoyable. The direct and persistent mention of “trenches”, “barricades”, and “1000 horses” provides a realistic description of the battlefield, and the story is full of detailed logistical planning. Their depictions of death coupled with paradoxical imagery (i.e. “…black embers of fire…") can be hyperbolic, poetic, and emotional. The occasional description of the setting such as the "drizzing rain" highlights the rawness of the moment: " we started in silence save the clank of the canteens now and then and barking of a wolf for it was growing dark and the moon had risen." Even though the Nelson brother’s tone tends to be more objective than subjective they make it clear that war can be messy. Amidst the overall concatenation of events, it is interesting to note the momentary descriptions of valor. Symbolism such as the “white horse” and the “capture of the flag” glorify war. It is evident that they enjoy the adventure of war and think is war is glorious but there is enough realism here to give some feeling of the atrocity that we call war.

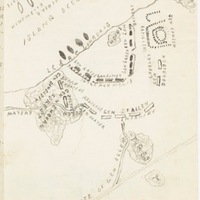

Battle of Popplington

A literary maturation of style is evident in the Nelson brother’s Battle of Popplington. The seemingly benign choice of particular adjectives unintentionally hyperbolizes the sheer blight of war. Perhaps the prime paradigm of the Nelson brother’s innocent syntactical choice is the mention of “noiseless march.” This choice of diction expresses the utter grim fate of the soldiers; as if they are zombies walking to their death. Moreover, the use of negative connotative words, such as “harassing” and “annoying”, to describe the white army is quite sarcastic. Considering the age of the Nelson brother’s, one cannot help but laud the astuteness of their craft. Despite the traditionally held view of children being sophomoric, the Nelson brother’s keen attention to detail is comparable to an adult. This claim is further substantiated with the description of the “awakening gun fire” as being the “Great Strike”. Considering the context of the piece as a whole, the “Great Strike” may represent a strike against humanity.

Little's War Adventures

One of the many Frgament pieces of the Nelson's histories of their "World" offers an imperialistic bravado that glorifies the prospect of wars. The literary piece serves as a refreshing adventure coupled by inklings of reality. The adventures of William Little and Bert Green demonstrates the imperialism that was once prevalent. The parallelism of colonization mirrors the sentiment of the time.

Considering the historical period, manifest destiny was ingrained in the American culture. As noted by the “8 dollars per acre” statement, the Nelson brothers referred to the colonization as being “settlers” buying land. An interesting yet subtle point made in this story is how the settlers claim this uncharted landscape. The labeling of continents (i.e. forest and new) suggests how colonizers see and name the land in ways that reflect their relationship to it. One of the illustrations represents two foot soldiers carrying guns while purchasing land. The most jarring aspect to this depiction is the need of having artillery. The glorification of violence to obtain land is seemingly “just”. To further explore this theme, the Nelson brothers depict the “20 year old men” as "sturdy." The word sturdy implies an aura of stoicism that is acceptable and perhaps necessary for colonization, and it is one of their favorite praises for their heroes. Moreover, the frequent mention of the “big continent” symbolizes the idea how there always is a new frontier to be inhabited. This cynical perspective, even though coming from children, is eerily consistent to what adults tend to adopt. It is evident from the Nelson brother’s description that imperialism has shaped their worldly view.

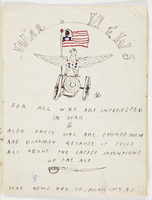

War News

The Nelson brother’s War News is an interesting perspective on war. Unlike the Thirty Day Wars, the War News is not ominous. War News is a periodical, and the Nelsons seem to know that during war time newspapers have the patriotic job of cheering on the war. The glorification of war is a pervading theme. The paper's attempts to engage a broad audience is evident through the myriad of themes discussed. For example, the cost of goods and services elicits tangibility, telling readers the cost of war. In addition, the detailed illustrations that accompany a given section are by far the most impactful. The illustrations celebrate the impressive technologies that were prevalent at the end of the 19th century. As a reader, I feel the empowerment of war because their glorification diminishes the bleakness of the matter.